In the realm of nutrition and digestive wellness, few components are as crucial—and as misunderstood—as dietary fiber. Long recognized for its role in promoting bowel regularity, fiber plays a far more complex and impactful part in our overall health than most realize. Not only does it contribute to a healthy gut, but it also influences blood sugar regulation, cholesterol levels, weight management, and even mental health through the gut-brain axis.

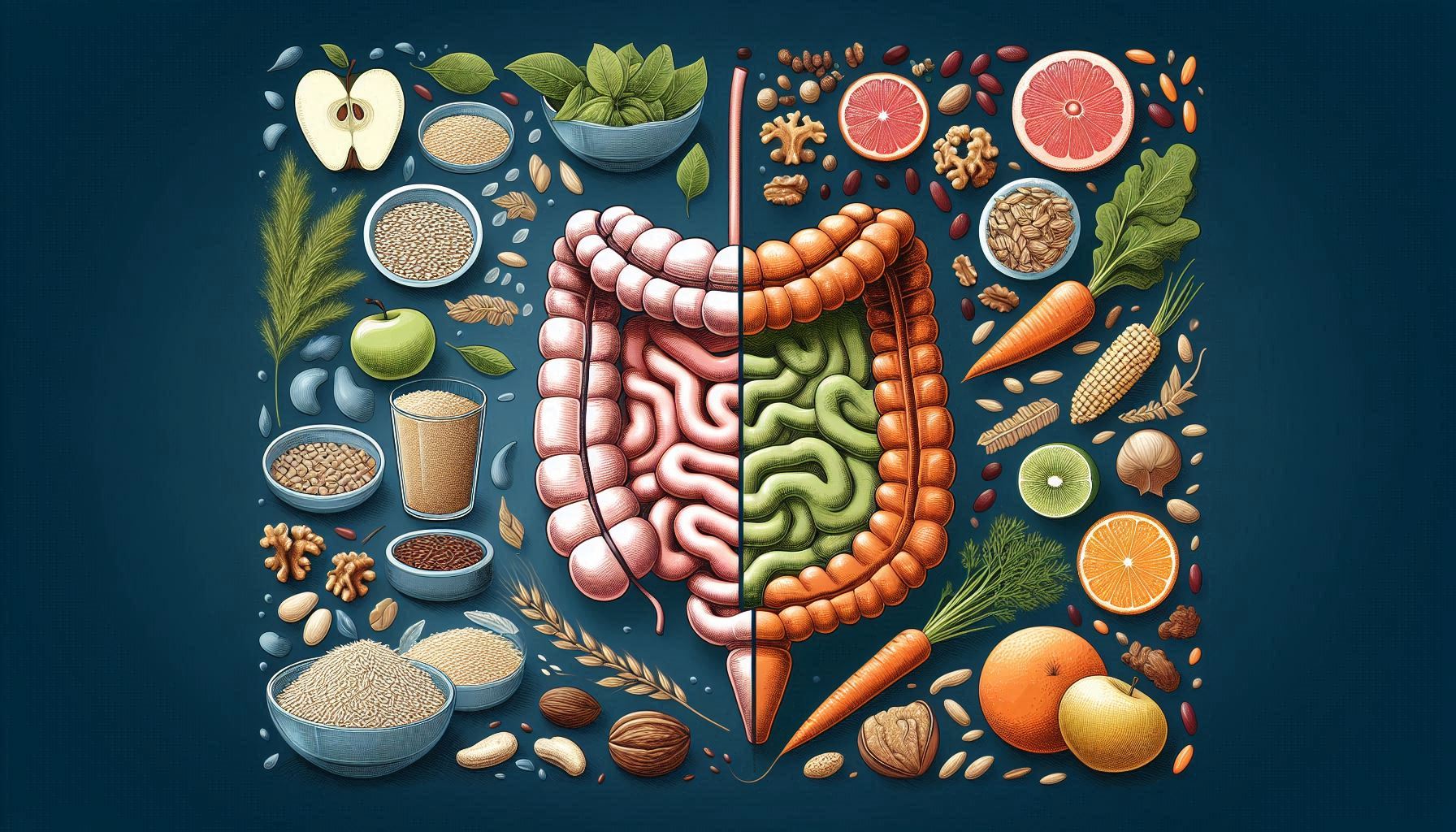

Dietary fiber is not a singular entity but a category of indigestible plant-based carbohydrates, broadly classified into soluble and insoluble fiber. These two types differ in structure, function, and health benefits—particularly concerning digestive health. Understanding the distinction between them is essential for making informed dietary choices and supporting long-term well-being.

What Is Dietary Fiber?

Dietary fiber refers to the parts of plant foods that the human digestive enzymes cannot break down. Unlike sugars and starches, fiber passes through the digestive system largely intact. While humans lack the enzymes to digest fiber, the gut micro biota—our internal ecosystem of trillions of microbes—thrives on it, especially soluble types.

Fiber is found in fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains, nuts, and seeds. It is divided into two main categories:

- Soluble fiber dissolves in water to form a gel-like substance.

- Insoluble fiber does not dissolve in water and adds bulk to stool.

Both types are essential, and each contributes differently to gut and overall health.

Soluble Fiber: The Gut’s Gentle Helper

How It Works

Soluble fiber dissolves in water and digestive fluids to form a viscous gel in the digestive tract. This gel slows digestion, allowing for better nutrient absorption and regulation of blood sugar levels. Soluble fiber also ferments in the colon, serving as a prebiotic—fuel for beneficial bacteria.

Digestive Benefits

- Slows gastric emptying: This prolongs satiety and stabilizes blood sugar.

- Feeds gut bacteria: Fermentation of soluble fiber produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate, which are vital for colon health and have anti-inflammatory properties.

- Eases bowel movements: It softens stool and helps manage diarrhea or loose stools by absorbing excess water.

Common Sources

- Oats and oat bran

- Barley

- Phylum husk

- Apples, oranges, and citrus fruits

- Carrots

- Beans, lentils, and peas

- Flaxseeds and chia seeds

Insoluble Fiber: The Digestive Tract’s Workhorse

How It Works

Insoluble fiber retains its form throughout digestion. It does not dissolve in water and passes through the gut relatively unchanged, which adds bulk to stool and speeds up intestinal transit time.

Digestive Benefits

- Promotes regularity: By increasing stool bulk and frequency, it helps prevent constipation.

- Supports intestinal motility: It stimulates the muscle contractions of the gut (peristalsis), reducing the risk of diverticulosis and hemorrhoids.

- Dilutes toxins: Its bulking effect can help dilute potential carcinogens and reduce transit time, limiting their contact with the intestinal lining.

Common Sources

- Whole wheat flour and bran

- Nuts and seeds

- Cauliflower and green beans

- Potatoes (with skin)

- Brown rice

- Dark leafy greens

How Soluble and Insoluble Fiber Work Together

While soluble and insoluble fibers serve different functions, they work synergistically to maintain digestive balance. A healthy diet should include both, as they provide complementary benefits.

For instance:

- A person with constipation may benefit more from insoluble fiber, while

- Someone with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or loose stools might benefit from more soluble fiber, especially from low-FODMAP sources.

Combining both types—like eating a whole apple (soluble fiber in the flesh, insoluble fiber in the skin)—ensures broad-spectrum digestive support.

Fiber, the Micro biome, and Digestive Health

The rise in research surrounding the gut micro biome has elevated fiber from a digestion aid to a cornerstone of gut health. Soluble fibers, especially prebiotic fibers like inulin and oligosaccharides, feed beneficial bacteria such as bifid bacteria and Lactobacilli.

These microbes ferment the fiber to produce SCFAs, which:

- Strengthen the gut lining

- Lower pH in the colon (inhibiting pathogenic bacteria)

- Modulate immune responses

- Reduce inflammation in conditions like ulcerative colitis and Cohn’s disease

Moreover, these SCFAs are now being studied for their neuroprotective and metabolic effects, tying gut health directly to brain function, mood regulation, and chronic disease prevention.

Recommended Daily Intake

According to health authorities like the Institute of Medicine, the recommended daily intake of fiber is:

- Men (under 50): 38 grams/day

- Women (under 50): 25 grams/day

- Men (over 50): 30 grams/day

- Women (over 50): 21 grams/day

Unfortunately, most people consume less than half the recommended amount.

Tips for Increasing Fiber Safely

- Go gradual: Increase fiber slowly to avoid bloating and gas.

- Stay hydrated: Fiber absorbs water—insufficient fluid intake can worsen constipation.

- Eat whole foods: Choose unprocessed, plant-based foods rich in natural fiber.

- Mix fiber types: Combine grains, legumes, fruits, and vegetables for a balance of soluble and insoluble fiber.

- Consider fiber supplements: If necessary, choose supplements like phylum, but use them under professional guidance.

Cautions and Considerations

While dietary fiber is a critical component of a healthy and balanced diet, not all digestive systems respond to fiber in the same way at all times. For individuals with certain gastrointestinal (GI) disorders or those recovering from surgery, the standard recommendations for fiber intake may need to be temporarily modified or tailored to individual tolerance levels.

Understanding how and when to adjust fiber intake is vital for anyone managing chronic or acute GI conditions. Below, we explore several key scenarios in which fiber modification may be necessary and offer insights into making informed, personalized choices.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): Fiber, But with Caution

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) is a functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by abdominal pain, bloating, gas, diarrhea, and/or constipation. While fiber can be helpful in managing symptoms—especially constipation-predominant IBS—not all types of fiber are tolerated equally.

Soluble vs. Insoluble Fiber in IBS

- Soluble fiber is generally better tolerated and can help regulate bowel movements and ease discomfort. Sources like oats, phylum husk, chia seeds, and cooked carrots are often recommended.

- Insoluble fiber, on the other hand, may exacerbate bloating, gas, and cramping, particularly during flare-ups. This type of fiber can increase stool bulk too aggressively, triggering irritation in sensitive individuals.

Personalized Fiber Strategy

- Introduce fiber gradually to assess tolerance.

- Avoid raw vegetables, bran, seeds, and high-residue grains during active IBS symptoms.

- Soluble fiber supplements (like phylum) may be beneficial, but synthetic fibers (like methylcellulose) may cause less fermentation and gas.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Balancing Nutrition with Inflammation

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)—which includes Cohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis—involves chronic inflammation of the GI tract. Unlike IBS, IBD is a structural disease with visible damage to the intestinal lining. Diet plays a crucial supportive role, especially during periods of active flare or remission.

Fiber in Flare vs. Remission

- During flares, patients are often advised to reduce insoluble fiber to minimize mechanical irritation of the bowel lining. High-residue foods like popcorn, nuts, raw fruits with skins, and cruciferous vegetables may cause pain, bleeding, or worsen diarrhea.

- During remission, fiber—especially fermentable soluble fiber—can help restore gut micro biota diversity, enhance stool consistency, and support mucosal healing.

Low-Residue or Low-Fiber Diets

In severe cases or during acute hospital admissions, a low-residue diet may be prescribed. This diet limits both insoluble and fermentable fibers to reduce stool volume and frequency.

Dietary Caution

- Introduce fiber slowly during remission.

- Prioritize well-cooked, peeled fruits and vegetables.

- Monitor for trigger foods, and avoid excessive fiber from unrefined grains during active disease.

Evidence Base:

According to Benjamin et al. (2011), while fiber restriction may be necessary during flares, a high-fiber diet may reduce the risk of relapse and support long-term remission in Cohn’s disease.

The Low-FODMAP Diet: Short-Term Elimination for Gut Relief

The Low-FODMAP diet, developed by Monish University, is a clinically proven approach for managing IBS and other functional GI symptoms. FODMAPs (Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharide’s, and Polios) are types of fermentable carbohydrates found in many fiber-rich foods.

The Fiber-FODMAP Overlap

Many high-fiber foods—such as wheat, rye, legumes, apples, and onions—contain FODMAPs. When consumed, these can ferment rapidly in the gut, leading to bloating, gas, and abdominal pain.

As a result:

- During the elimination phase, fiber intake may unintentionally decrease.

- Reintroduction must be carefully structured to balance fiber needs with symptom control.

Low-FODMAP, High-Fiber Options

To maintain gut health during FODMAP elimination, individuals are encouraged to include:

- Carrots, zucchini, and spinach (low-FODMAP vegetables)

- Chia and flaxseeds

- Gluten-free oats

- Firm bananas and strawberries

Clinical Guidance

Dietitians trained in the Low-FODMAP protocol can help patients identify fiber-rich, low-FODMAP alternatives, ensuring nutritional adequacy throughout the process.

Post-Surgical Recovery: Temporary Fiber Restrictions

After abdominal, colorectal, or gastrointestinal surgery, the digestive system needs time to heal and re-establish function. In these cases, fiber intake is typically restricted short-term to reduce mechanical and fermentative stress on the gut.

Common Postoperative Scenarios

- Colorectal surgery: May require a low-fiber diet to prevent bowel obstruction.

- Bowel resection: Fiber is often reintroduced slowly as the gut adapts to reduced surface area.

- Ileostomy or colostomy: Insoluble fiber may clog the stoma or increase output volume initially.

Diet Progression after Surgery

- Clear liquids (immediate post-op phase)

- Low-residue or low-fiber diet (transition phase)

- Gradual reintroduction of soluble fiber (recovery phase)

Monitoring is essential, and dietary fiber is typically reintroduced under medical supervision once the GI tract resumes normal motility and tolerance improves.

Diverticulitis and Diverticulosis: Rethinking Old Myths

Diverticulosis is the formation of small pouches (diverticula) in the colon wall. When these pouches become inflamed or infected, the condition is called diverticulitis. Historically, patients were advised to avoid fiber, nuts, and seeds, but modern evidence suggests otherwise.

Current Understanding

- In flare-ups: A low-fiber or clear liquid diet may help reduce irritation.

- In remission: A high-fiber diet is actually protective and helps prevent recurrence.

Updated Recommendations

- Emphasize whole grains, fruits, and vegetables after inflammation subsides.

- Reintroduce fiber slowly and monitor symptoms.

- There is no need to avoid seeds or nuts, unless specifically triggering.

General Recommendations for Fiber Modification

When to Adjust Fiber Intake: Key Indicators

- Persistent bloating, pain, or changes in stool pattern

- Acute disease flare-ups (IBD, diverticulitis)

- Pre- or post-surgical digestive care

- Diet therapy (e.g., FODMAP elimination)

Guidelines for Safe Fiber Use in Sensitive Populations

- Start low, go slow: Gradually build up to the recommended intake (25–38 g/day).

- Hydrate adequately: Always pair fiber increases with more water to reduce constipation and bloating.

- Cook vegetables: Soft-cooked veggies are easier to tolerate than raw.

- Individualize plans: What works for one person may not suit another.

Fiber with Flexibility

Dietary fiber is indispensable for digestive health, but like any nutritional strategy, it must be personalized. Individuals with IBS, IBD, or those recovering from surgery may benefit from adjusting the type, amount, and timing of fiber intake based on symptom patterns and clinical context.

Rather than viewing fiber as a universal prescription, it should be seen as a powerful therapeutic tool—one that must be customized to the individual’s physiology and current health status. Collaborating with a registered dietitian or gastroenterologist ensures that fiber remains not only a health-promoting nutrient but also a well-tolerated and sustainable part of any long-term wellness plan.

Conclusion

Soluble and insoluble fiber is not only essential to digestive function—they serve as cornerstones of long-term health and disease prevention. These two types of dietary fiber operate through distinct yet complementary mechanisms: soluble fiber slows digestion and nourishes the gut micro biota, while insoluble fiber promotes efficient bowel movement and detoxification. When consumed in balance, they work synergistically to support optimal gastrointestinal function, metabolic regulation, and immune health.

A growing body of research continues to highlight the far-reaching effects of dietary fiber, extending beyond digestion to include the regulation of blood sugar, cholesterol levels, weight control, and even cognitive function through the gut-brain axis. Moreover, fiber-rich diets have been associated with a lower risk of developing chronic conditions such as type 2 diabetes, heart disease, colorectal cancer, and inflammatory bowel diseases.

One of fiber’s most profound contributions lies in its ability to feed the beneficial bacteria in the gut. Through fermentation of soluble fibers, gut microbes produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, which possess anti-inflammatory and protective properties. These compounds help maintain the integrity of the intestinal lining, reduce systemic inflammation, and play a critical role in immune modulation. This dynamic relationship between fiber and the micro biome emphasizes why fiber is more than just a digestive aid—it is a foundational nutrient for whole-body health.

Despite its importance, dietary fiber remains one of the most under-consumed nutrients in the modern diet. The widespread availability of ultra-processed, low-fiber foods has contributed to a global fiber deficiency, often referred to as the “fiber gap.” Bridging this gap requires conscious dietary choices—replacing refined grains with whole grains, incorporating a diverse array of fruits and vegetables, adding legumes and seeds, and being mindful of daily fiber targets.

Embracing fiber-rich foods is one of the simplest yet most impactful acts of self-care. It doesn’t require drastic dietary overhauls—small, consistent changes can yield substantial benefits. Whether your goal is to improve regularity, support your gut micro biome, manage weight, or reduce the risk of chronic disease, fiber is a nutrient that delivers sustained value from the inside out.

In a world dominated by fast food and quick fixes, choosing whole, fiber-rich foods is an act of nutritional wisdom and long-term health investment. By making fiber a daily priority, you empower your digestive system, fortify your overall health, and take a proactive step toward lifelong wellness.

SOURCES

Anderson, J.W., et al. (2009) – Health benefits of dietary fiber. Nutrition Reviews.

Slaving, J.L. (2013) – Fiber and prebiotics: mechanisms and health benefits. Nutrients.

Stephen, A.M., et al. (2017) – Dietary fiber in Europe: current state of knowledge on definitions, sources, recommendations, intakes and relationships to health. Nutrition Research Reviews.

Reynolds, A.N., et al. (2019) – Effects of dietary fiber on glycemic control and body weight in type 2 diabetes. The Lancet.

Marjorie, J.W., & McKeon, N.M. (2017) – Understanding the physics of functional fibers in the gastrointestinal tract. Nutrition Today.

Institute of Medicine (IOM) (2005) – Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids.

USDA (2020) – Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020–2025.

National Institutes of Health (NIH) (2021) – Fiber: Medline plus Nutrition Guide.

World Health Organization (WHO) (2003) – Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases.

Schulze, M.B., et al. (2007) – Fiber and risk of colorectal cancer. Journal of the American Medical Association.

Silk, D.B.A., et al. (2009) – Prebiotics and the human colonic micro biota. British Journal of Nutrition.

Birth, D.F., et al. (2013) – Dietary fiber and cancer prevention. Nutrition.

Make, K., et al. (2018) – The impact of dietary fiber on gut micro biota in health and disease. Cell Host & Microbe.

Scott, K.P., et al. (2013) – The influence of diet on the gut micro biota. Pharmacological Research.

Tung land, B.C., & Meyer, D. (2002) – No digestible olio- and polysaccharides (dietary fiber): their physiology and role in human health and food. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety.

Kumar, N., et al. (2020) – Dietary fiber and human health: a review. Journal of Food Biochemistry.

Vixen, V., et al. (2011) – Viscous fiber improves glycemic control. Diabetes Care.

Brownlee, I.A. (2011) – The physiological roles of dietary fiber. Food Hydrocolloids.

Roberfroid, M. (2007) – Prebiotics: the concept revisited. The Journal of Nutrition.

Jones, J.M. (2014) – CODEX-aligned dietary fiber definitions help to bridge the ‘fiber gap.’ Nutrition Journal.

Gibson, G.R., et al. (2010) – Dietary prebiotics: current status and new definition. Food Science and Technology Bulletin: Functional Foods.

Guarneri, F., & Malagelada, J.R. (2003) – Gut flora in health and disease. The Lancet.

Cummings, J.H., & Macfarlane, G.T. (1997) – Role of intestinal bacteria in nutrient metabolism. JPEN.

Delzenne, N.M., et al. (2005) – The prebiotic concept: in vivo evidence for health benefits. British Journal of Nutrition.

Tap sell, L.C., et al. (2010) – Health benefits of dietary fiber. Nutrition & Dietetics.

HISTORY

Current Version

June 18, 2025

Written By

ASIFA