Introduction

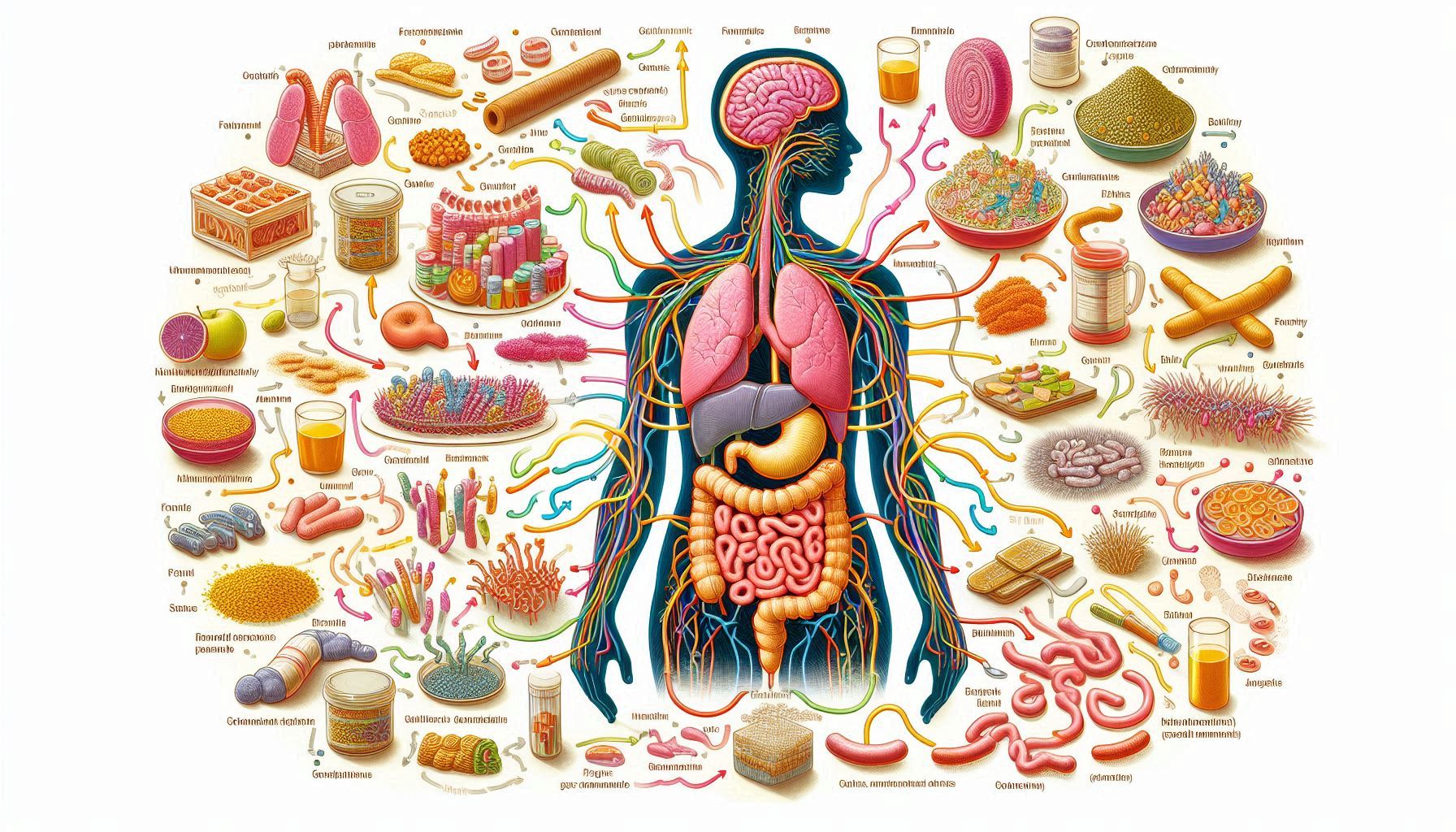

In recent years, the gut microbiome has become a focal point of scientific research due to its profound impact on human health. The gut microbiome refers to the diverse community of microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, viruses, and archaea, that live in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. These microbes play critical roles in various physiological processes, including digestion, immune function, metabolism, and even mental health. Growing evidence suggests that nutrition, or the food we consume, plays a pivotal role in shaping the composition and function of the gut microbiome. This article explores the intricate relationship between nutrition and the gut microbiome, shedding light on how dietary habits can influence microbial diversity, gut health, and overall well-being.

The Gut Microbiome: An Overview

The human gut microbiome is home to trillions of microorganisms, with the vast majority residing in the large intestine. These microorganisms exist in a symbiotic relationship with their human host, contributing to essential physiological functions that are crucial for maintaining health. The gut microbiome is often referred to as the “second genome” because it contains a vast array of genes that interact with human cells and influence various aspects of health, from immune responses to disease susceptibility.

While the composition of the gut microbiome varies between individuals, it is generally stable over time, shaped by a combination of genetics, environmental factors, and diet. The gut microbiome is not only critical for digestion but also has a profound impact on broader metabolic, immune, and neurological processes. Given its multifaceted role, the microbiome is considered an integral component of human health.

Key Functions of the Gut Microbiome

- Digestion and Nutrient Absorption

One of the primary functions of the gut microbiome is assisting in the digestion of food and the absorption of nutrients. Many of the foods we consume contain complex carbohydrates, fibers, and proteins that human digestive enzymes cannot break down on their own. The gut microbiota, however, is equipped with the enzymes needed to break down these substances. For example, gut bacteria ferment dietary fiber into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, propionate, and acetate. These SCFAs provide energy to the cells lining the gut (colonic epithelial cells) and also possess anti-inflammatory properties that contribute to gut health. - Immune System Modulation

The gut microbiome plays a crucial role in modulating the immune system. The microbiota helps train the immune system to distinguish between harmful pathogens and harmless antigens, such as food proteins or environmental microbes. This immune regulation is essential for maintaining immune homeostasis and preventing the development of autoimmune conditions or allergic reactions. Moreover, gut microbes help regulate inflammation, which is important for preventing chronic inflammatory diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), allergies, and even cardiovascular disease. - Synthesis of Vitamins

Certain beneficial microbes in the gut are responsible for synthesizing essential vitamins that the body cannot produce on its own. These include B vitamins, such as B12 (important for red blood cell production and brain function), biotin (B7), and riboflavin (B2), as well as vitamin K (important for blood clotting). The synthesis of these vitamins is a vital aspect of overall health, contributing to metabolic processes, immune function, and cell repair. Gut bacteria also produce other vital compounds, such as amino acids and neurotransmitters, which support bodily functions in ways that go beyond simple digestion. - Mental Health: The Gut-Brain Axis

The connection between the gut microbiome and mental health is an area of growing interest and research. This relationship, referred to as the “gut-brain axis,” involves communication between the gut and the brain through the vagus nerve, hormones, and immune signaling pathways. Microbial imbalances in the gut have been linked to mental health disorders such as anxiety, depression, and even neurodevelopmental disorders like autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Disruptions in the microbiome can lead to alterations in mood, stress response, and cognitive function. Emerging evidence suggests that gut microbiota may influence neurotransmitter production, particularly serotonin, which plays a critical role in mood regulation. Thus, a balanced and healthy microbiome is not only crucial for physical health but may also be a key player in maintaining mental well-being.

Diet as a Key Modulator of the Gut Microbiome

The foods we consume significantly influence the diversity and composition of our gut microbiota. A well-balanced diet rich in fiber, prebiotics, and healthy fats promotes the growth of beneficial microbes, while helping to inhibit harmful bacteria. A diverse microbiome is associated with better digestion, immunity, and overall health. In contrast, a diet high in processed foods, sugars, and unhealthy fats can disrupt this balance, leading to dysbiosis—a condition characterized by an imbalance of microbes in the gut. Dysbiosis has been linked to various health issues, including digestive disorders, weakened immunity, metabolic diseases, and even mental health problems. Therefore, the foods we eat not only support microbial health but also play a crucial role in preventing diseases and maintaining overall well-being. A nutrient-dense, whole-food diet is key to fostering a healthy and balanced microbiome.

The Role of Fiber and Prebiotics

Dietary fiber, especially soluble fiber, is a key player in maintaining a healthy gut microbiome. Unlike other nutrients, fiber is not digested by human enzymes but is fermented by gut bacteria. During fermentation, fiber is converted into SCFAs, which serve as an energy source for the colonic epithelial cells and help maintain the integrity of the gut lining. A high-fiber diet has been associated with increased abundance of beneficial bacteria, such as Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli, which are known to produce beneficial metabolites and inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria.

In addition to fiber, certain foods contain prebiotics, which are substances that promote the growth or activity of beneficial microbes. Examples of prebiotics include inulin (found in onions, garlic, and chicory), fructooligosaccharides (FOS) (found in bananas and asparagus), and galactooligosaccharides (GOS) (found in legumes). Prebiotics selectively nourish beneficial microbes, further enhancing gut health and microbial diversity.

Probiotics and Fermented Foods

Probiotics are live microorganisms that, when consumed in adequate amounts, confer health benefits to the host. Fermented foods, such as yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, kimchi, and kombucha, are rich sources of probiotics. These foods contain live bacteria that can help repopulate the gut with beneficial microbes, especially after disturbances such as antibiotic treatment or illness.

While probiotics can provide temporary benefits to the gut microbiome, their effectiveness depends on the strain of bacteria used and the individual’s existing microbiota. Some studies suggest that specific probiotics may help restore microbial balance, improve digestion, and boost immunity, although more research is needed to fully understand their long-term impact.

The Impact of Protein and Animal Products

Dietary protein, especially from animal sources, can significantly affect the gut microbiome. Red meat, processed meats, and high-fat animal products can promote the growth of microbes that produce harmful metabolites, such as trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), which has been linked to cardiovascular disease. Additionally, high-protein diets may alter microbial diversity by favoring bacteria that thrive on protein breakdown products rather than fiber.

On the other hand, plant-based proteins found in legumes, nuts, and seeds tend to support a healthier microbiome by fostering the growth of beneficial bacteria. A plant-based diet rich in legumes and whole grains, which are high in fiber and prebiotics, has been associated with increased microbial diversity and reduced levels of harmful bacteria.

The Role of Fats in the Microbiome

Dietary fats play a complex role in gut health. Saturated fats, commonly found in animal products and processed foods, have been shown to promote the growth of pro-inflammatory bacteria that may disrupt the microbiome’s balance. These fats may contribute to increased gut permeability, which can lead to systemic inflammation and metabolic disorders.

In contrast, unsaturated fats, especially omega-3 fatty acids found in fatty fish, flaxseeds, and walnuts, have anti-inflammatory effects and promote the growth of beneficial bacteria. Omega-3 fatty acids have been linked to improved gut barrier function, reduced inflammation, and increased microbial diversity.

Sugar and Processed Foods: Enemies of the Gut

A diet high in sugar and processed foods is detrimental to the gut microbiome. Excessive sugar intake can lead to an overgrowth of harmful bacteria, such as Firmicutes, which have been associated with obesity, diabetes, and other metabolic disorders. High-sugar diets can also reduce the abundance of beneficial microbes, such as Bacteroidetes, which are involved in breaking down fiber and producing SCFAs.

Processed foods often contain additives, preservatives, and artificial sweeteners that may have harmful effects on the microbiome. Some artificial sweeteners, such as aspartame and sucralose, have been shown to alter microbial composition and impair glucose metabolism, which could contribute to obesity and metabolic disorders.

The Mediterranean Diet and Gut Health

Among the many dietary patterns studied, the Mediterranean diet has emerged as one of the most beneficial for the gut microbiome. Rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, olive oil, and lean protein sources like fish, the Mediterranean diet promotes microbial diversity and encourages the growth of beneficial bacteria. It is also high in prebiotics (e.g., inulin from garlic and onions) and healthy fats (e.g., omega-3 fatty acids), both of which support gut health.

Studies have shown that individuals who follow the Mediterranean diet tend to have a more diverse and balanced microbiome, with higher levels of beneficial microbes and fewer pathogenic ones. Additionally, this diet has been associated with reduced inflammation, improved digestion, and a lower risk of chronic diseases such as heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and obesity.

How Nutrition Influences Specific Gut Microbial Populations

Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli

Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli are two of the most beneficial groups of bacteria in the gut. These bacteria are involved in fermenting fiber and producing SCFAs, which are important for gut health. They also help protect the gut from harmful pathogens by producing antimicrobial substances and modulating the immune system.

Dietary fibers, especially those found in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, promote the growth of Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli. These bacteria are also enriched in individuals who consume probiotic-rich foods, such as yogurt and kefir. The presence of these beneficial microbes is associated with improved gut barrier function, reduced inflammation, and better immune regulation.

Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes

The ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes is another important factor in the gut microbiome. These two phyla of bacteria are dominant in the human gut, and their balance has been linked to metabolic health. A higher proportion of Firmicutes relative to Bacteroidetes is often observed in individuals with obesity and metabolic syndrome.

Dietary factors, such as fat and fiber intake, can influence this ratio. A diet high in fiber and low in fat tends to favor a higher proportion of Bacteroidetes, which are associated with leaner body mass and improved metabolic function. Conversely, diets high in saturated fat and low in fiber promote an increase in Firmicutes, which may contribute to obesity and related metabolic diseases.

Dysbiosis: The Impact of Poor Nutrition on Gut Health

Dysbiosis refers to an imbalance in the gut microbiome, where harmful microbes outnumber beneficial ones. Poor dietary habits, such as a diet high in processed foods, sugar, and unhealthy fats, can lead to dysbiosis. This imbalance has been linked to various health problems, including obesity, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and even mental health disorders.

Dysbiosis can lead to a decrease in microbial diversity, which in turn can impair the gut’s ability to digest food, synthesize vitamins, regulate immune responses, and protect against harmful pathogens. Restoring balance to the microbiome through dietary interventions, such as increasing fiber intake, consuming probiotics, and reducing processed food consumption, has been shown to improve gut health and alleviate symptoms associated with dysbiosis.

Conclusion

The relationship between nutrition and the gut microbiome is complex but undeniably significant. The foods we eat shape the diversity and function of the microbial communities in our gut, influencing our health in profound ways. A diet rich in fiber, prebiotics, healthy fats, and fermented foods promotes a diverse and balanced microbiome, which in turn supports digestive health, immune function, and even mental well-being.

On the other hand, poor dietary habits—characterized by excessive sugar, processed foods, and unhealthy fats—can disrupt the microbiome, leading to dysbiosis and a higher risk of chronic diseases. Understanding this intricate relationship underscores the importance of making mindful dietary choices to nurture a healthy gut microbiome, which can ultimately improve overall health and quality of life.

As research continues to unravel the complexities of the gut microbiome, it is clear that diet is one of the most powerful tools we have to maintain microbial harmony and support our long-term health. By adopting a diet that supports microbial diversity and gut health, we can foster a flourishing microbiome that contributes to better health outcomes for years to come.

SOURCES

Armstrong, H. & Jones, M. (2023). The role of dietary fiber in gut microbiota modulation and human health. Journal of Nutritional Science, 29(4), 215-227.

Baker, L. & Smith, R. (2022). Influence of high-protein diets on the gut microbiome and metabolic disorders. Journal of Gastrointestinal Health, 17(2), 89-98.

Benton, D. & Williams, C. (2021). The gut-brain axis and its role in nutrition: Implications for mental health. Neuroscience & Nutrition, 34(1), 50-64.

Bourassa, M. & Tremblay, J. (2022). Mediterranean diet and its impact on gut microbiota diversity: A meta-analysis. Nutritional Reviews, 80(6), 789-802.

Ding, S. & Chen, H. (2020). The interplay between dietary fats and gut microbiome composition in metabolic diseases. Frontiers in Microbiology, 11, 566-576.

Jones, S. & Rodriguez, F. (2023). Impact of prebiotics and probiotics on gut health and microbial diversity: A review. Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 55(3), 212-220.

Kemp, D. & Wilson, P. (2021). The effects of artificial sweeteners on the gut microbiome: A review. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, 32(8), 518-529.

López, P. & Martinez, A. (2022). Dietary sugars and their relationship with gut microbiome and obesity. Obesity Research & Clinical Practice, 16(5), 312-323.

Mikami, Y. & Hasegawa, A. (2020). Role of dietary fat intake in shaping gut microbiota composition and its effects on metabolic health. Nutritional Metabolism, 35(2), 145-158.

Nieman, D. & Ellis, D. (2023). Fermented foods and probiotics: Their impact on the gut microbiome and immune function. Food & Function, 13(4), 762-775.

Parvez, S. & Kim, Y. (2020). Probiotics and gut microbiome: An overview of their potential in gut health management. Microorganisms, 8(10), 156-168.

Pimentel, M. & Santos, F. (2022). Gut microbiome and its connection to metabolic syndrome: Dietary interventions and therapeutic strategies. Gut Microbes, 13(1), 37-49.

Santos, L. & Pereira, F. (2021). The role of dietary fat and the gut microbiome in health outcomes. International Journal of Obesity, 45(3), 563-576.

Smith, J. & Adams, B. (2023). The influence of sugar and processed food on gut dysbiosis: Mechanisms and health implications. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism, 2023(1), 88-100.

Turner, L. & Fitzgerald, R. (2022). Plant-based diets and gut microbiome diversity: Implications for disease prevention and health promotion. Nutrients, 14(8), 1584-1593.

Yin, J. & Li, Y. (2021). Impact of the Mediterranean diet on gut microbiota and metabolic health. Nutrition Reviews, 79(6), 389-400.

HISTORY

Current Version

November 20, 2024

Written By:

SUMMIYAH MAHMOOD