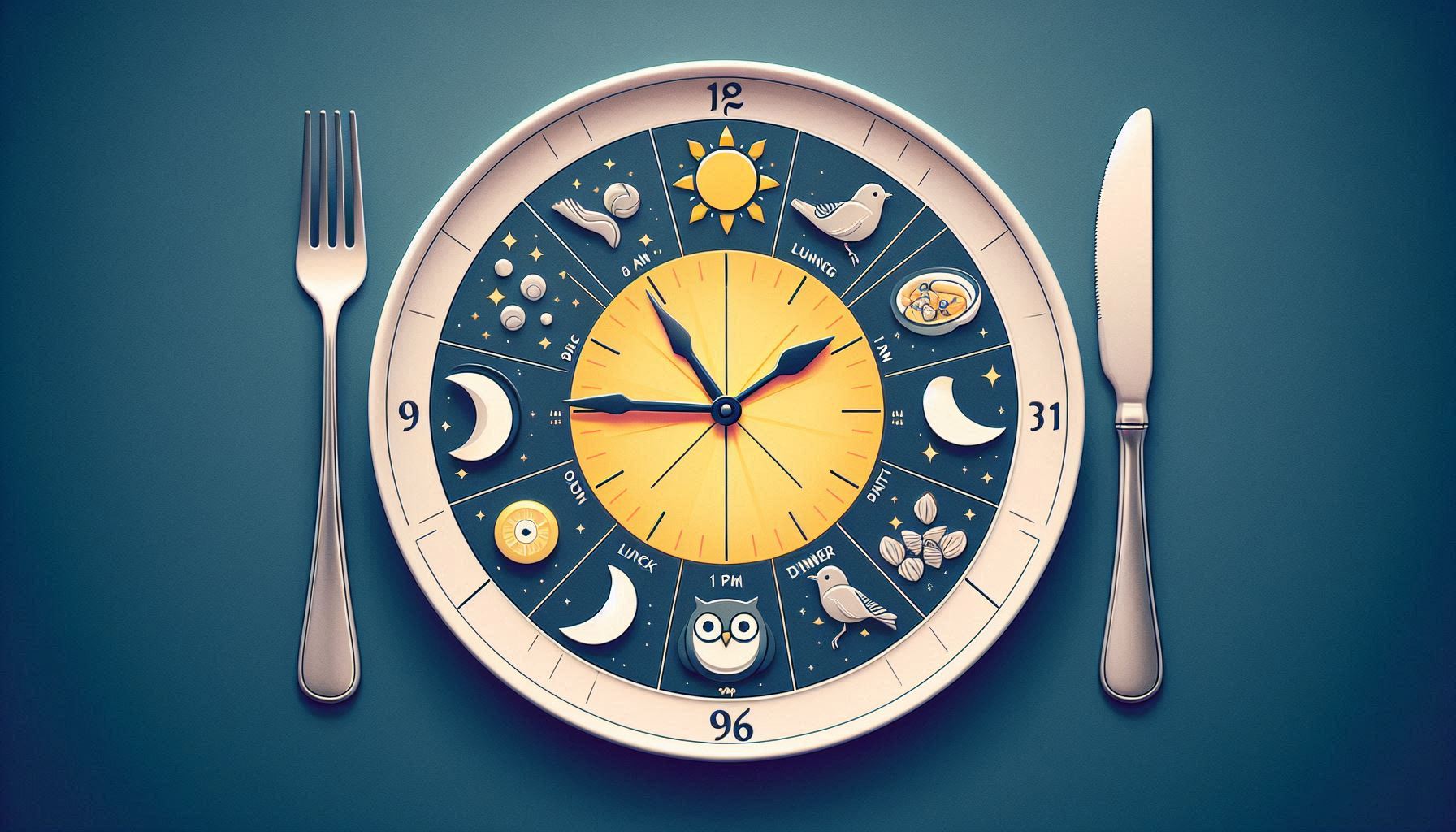

In the pursuit of optimal health, nutrition and sleep are often addressed separately. However, cutting-edge chrononutrition research reveals that when you eat may be just as vital as what you eat. Each of us operates according to a unique biological rhythm known as a phonotype, which governs sleep-wake cycles and energy levels. Aligning your meals with your phonotype isn’t just a bio hacking trend—it’s a science-backed strategy to enhance metabolic health, support weight management, and improve cognitive performance.

Understanding Phonotypes

In the pursuit of optimal health, the timing of when we eat has emerged as a critical piece of the puzzle, alongside what and how much we eat. This concept is encapsulated in the emerging science of chrononutrition, which examines the relationship between our internal biological clocks and our eating patterns. Chrononutrition draws on circadian biology, metabolism, and nutrition to develop strategies that align food intake with the body’s natural rhythms, potentially reducing the risk of chronic diseases and improving overall well-being.

A crucial component of chrononutrition is the concept of phonotypes—individual variations in circadian rhythm that affect when we feel most alert, energetic, or sleepy. Understanding your phonotype can help tailor you’re eating schedule to your body’s natural highs and lows in metabolism and hormone production.

What Are Phonotypes?

Phonotypes reflect your internal body clock and determine your natural propensity for sleeping and waking. Essentially, they indicate whether you’re a “morning person” or a “night owl.” Phonotypes are categorized into three primary types:

- Morning Type (Larks): Wake early, experience peak energy mid-morning, and wind down by early evening.

- Evening Type (Owls): Prefer late nights, peak in the late afternoon or evening, and find early mornings challenging.

- Intermediate Type (Hummingbirds): Exhibit patterns that fall between the two extremes.

Influencing Factors

Phonotype is not fixed and is influenced by multiple variables:

- Genetics: Genetic variants, such as in the PER3 gene, influence phonotype.

- Age: Adolescents tend to be more evening-oriented, whereas older adults gravitate toward boringness.

- Lifestyle: Exposure to light, work schedules, and social obligations can modify your expressed phonotype.

Identifying Your Phonotype

You can identify your phonotype through validated tools like the Munich Phonotype Questionnaire (MCTQ) or quizzes such as Dr. Michael Reus’s Power of When.

Introduction to Chrononutrition

Chrononutrition is the study of how food timing impacts health, based on circadian biology. The body’s central clock resides in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the brain, while peripheral clocks are found in organs such as the liver, pancreas, and adipose tissue.

Key Principles of Chrononutrition

- Insulin Sensitivity: Insulin sensitivity is higher in the morning, suggesting that carbohydrate intake should be concentrated earlier in the day.

- Night Eating Risks: Eating late at night disrupts glucose metabolism, increases fat storage, and negatively impacts sleep.

- Circadian Entrainment: Regular meal timing helps synchronize peripheral clocks, enhancing metabolic harmony.

Phonotype-Based Eating Strategies

Morning Types (Larks)

- Best Eating Window: 7 a.m. – 6 p.m.

- Strategy: Front-load calories, prioritize breakfast, and eat a light dinner.

- Risks: Avoid skipping breakfast, as this group thrives on morning nutrition.

Evening Types (Owls)

- Best Eating Window: 10 a.m. – 8 p.m.

- Strategy: Shift eating window forward gradually, avoid very late-night meals.

- Risks: Increased tendency to consume late-night snacks; prone to circadian misalignment.

Intermediate Types (Hummingbirds)

- Best Eating Window: 8 a.m. – 7 p.m.

- Strategy: Balanced meals distributed throughout the day, adaptable to various schedules.

- Strengths: Flexibility to shift toward morning or evening timing as needed.

Scientific Evidence and Mechanisms

Metabolic Implications

- Jakubowicz et al. (2013): Front-loaded calorie distribution improved weight loss and glucose control.

- Morris et al. (2015): Diurnal variation in glucose tolerance shows superior morning metabolic efficiency.

Hormonal Regulation

- Meal timing influences hormones such as ghrelin (hunger), lepton (satiety), insulin, and cortisol.

- Evening eating disrupts melatonin secretion, impairing sleep and metabolic processing.

Peripheral Clock Synchronization

- Stockman et al. (2001): Demonstrated that food intake resets peripheral clocks independently of the SCN.

Special Populations

Shift Workers

Shift work leads to chronic circadian misalignment. Chrononutrition interventions include:

- Light therapy

- Strategic meal timing (e.g., eating meals only during day shifts)

- Avoiding heavy meals during night shifts

Travelers

- Jet lag disrupts meal and sleep timing.

- Gradual adjustment of meal times before travel can ease transitions.

Adolescents and College Students

- Naturally lean toward eveningness.

- Chrononutrition strategies can support metabolic health and academic performance.

Practical Applications

Tips to Align Meals with Circadian Rhythms

- Eat Breakfast Within 1 Hour of Waking

- Keep Meal Times Consistent Daily

- Avoid Late-Night Eating

- Use Time-Restricted Eating (TRE) within your phonotype window

- Plan Meals Around Work and Social Life without disrupting rhythm

Caffeine and Alcohol

- Limit caffeine after 2 p.m. to preserve melatonin rhythms.

- Alcohol can disrupt sleep architecture and should be timed carefully, especially for evening phonotypes.

Emerging Research

- Time-restricted eating (TRE) shows promise for improving insulin sensitivity and reducing weight.

- Personalized nutrition algorithms may use genetic and phonotype data to optimize meal timing.

- Ongoing studies explore the use of chrononutrition to manage type 2 diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular risk.

- Phonotypes and chrononutrition offer a powerful, evidence-based approach to optimizing health by syncing food intake with your body’s internal clock. As our understanding of circadian biology deepens, so too does the potential to apply these insights to personalized nutrition, disease prevention, and performance enhancement. Whether you’re a morning lark or a night owl, aligning your meals with your body’s rhythms could be one of the most accessible and effective strategies for long-term health.

Meal Timing Recommendations by Phonotype

For Morning Types:

- Breakfast: Within 30–60 minutes of waking; high in protein and complex carbs.

- Lunch: Around 12 PM; focus on balanced macronutrients.

- Dinner: By 6–7 PM; lighter, lower in carbs to avoid energy dips.

- Avoid: Late-night snacks or caffeine after 2 PM.

For Evening Types:

- Breakfast: Delay until hunger naturally arises, perhaps 9–10 AM.

- Lunch: Around 1–2 PM; robust with protein and fiber.

- Dinner: Around 8 PM, but avoid eating after 9 PM.

- Avoid: Skipping breakfast regularly, as it may lead to overcompensation later.

For Intermediate Types:

- Breakfast: By 8–9 ARE; moderate in size.

- Lunch: Around 12:30–1:30 PM.

- Dinner: Around 7 PM.

- Avoid: Eating within 2 hours of bedtime.

Nutrition Timing and Hormonal Rhythms

Hormones such as cortisol, melatonin, insulin, ghrelin, and lepton all follow a circadian pattern. Eating in sync with their natural rhythms optimizes satiety, fat storage, and energy expenditure:

- Cortisol: Peaks in the morning; supports energy and blood sugar regulation.

- Insulin: More efficient in the morning.

- Melatonin: Increases at night; eating during its rise can impair glucose metabolism.

Phonotype and Intermittent Fasting

Intermittent fasting (IF) strategies can be personalized:

- Morning Types: Early time-restricted feeding (e.g., 8 AM–4 PM) supports their rhythm.

- Evening Types: Slightly delayed windows (e.g., 10 AM–6 PM) may be more sustainable.

- Hummingbirds: Flexible IF approaches work well.

Challenges and Considerations

In our fast-paced world, mealtimes are often dictated more by schedules than by our body’s internal signals. However, emerging research in chrononutrition—the science of how meal timing impacts health—shows that when we eat can be just as important as what we eat. This article explores how aligning meals with your circadian rhythm can improve metabolism, energy levels, and overall well-being. We also dive into challenges like shift work, travel, and social jet lag, and provide practical, research-backed strategies to help you eat in harmony with your internal clock.

Your circadian rhythm is your body’s internal clock, roughly following a 24-hour cycle, influenced primarily by light and darkness. Nearly every cell in your body, including those in the digestive system, has its own clock. These biological clocks regulate hormones, digestion, appetite, and energy utilization throughout the day.

Disruptions in circadian rhythms—due to erratic schedules, late-night eating, or shift work—can lead to:

- Impaired glucose tolerance

- Increased fat storage

- Hormonal imbalances

- Sleep disturbances

- Higher risks of obesity and chronic diseases

Eating in alignment with your circadian rhythm supports optimal metabolism and enhances your body’s natural rhythms.

Common Circadian

1. Social Jet Lag

Social jet lag occurs when there’s a mismatch between your biological clock and social obligations, like staying up late or waking early for work or social events. This misalignment often leads to irregular meal times, late-night snacking, and inconsistent eating patterns.

Impact:

- Alters appetite-regulating hormones (ghrelin and lepton)

- Increases cravings for high-calorie foods

- Disrupts insulin sensitivity, especially with nighttime eating

2. Shift Work

Shift workers often eat at biologically inappropriate times due to non-traditional work hours. The body isn’t designed to digest food efficiently late at night, leading to metabolic stress.

Challenges for Shift Workers:

- Higher risk of metabolic syndrome

- Elevated blood sugar after meals

- Disrupted sleep from poorly timed caffeine or meals

Solution: Customized nutrition planning is essential—strategically timing meals to minimize circadian misalignment can mitigate health risks.

3. Travel across Time Zones

Crossing time zones disrupts both sleep and eating schedules, throwing off your body’s digestive cues.

Impact:

- Jet lag impairs appetite and digestion

- Increased risk of gastrointestinal issues

- Insulin response is delayed, especially if eating late at night in the new time zone

Tip: Gradually adjusting meal and sleep times before travel and sticking to local time upon arrival helps recalibrate your rhythm.

Practical Tips to with Your Body Clock

1. Identify Your Phonotype

Everyone has a unique phonotype—essentially, whether you’re a “morning lark” or a “night owl.” Understanding your natural sleep-wake preference helps determine your peak energy hours.

How to Identify It:

- Use online phonotype quizzes (like the Munich Phonotype Questionnaire)

- Track your natural sleep and energy patterns for two weeks in a diary

Why It Matters:

Meal timing based on your phonotype enhances energy and supports better metabolic outcomes.

2. Stick to Consistent Meal Times

Eating meals at consistent times each day helps regulate hunger hormones and reinforces your internal clock. Irregular eating, especially skipping breakfast and eating late at night, has been linked to weight gain and poor glucose control.

Tip: Anchor your meals around your natural rhythm—if you’re most active in the morning, have a substantial breakfast and lighter dinner.

3. Front-Load Your Calories

Your body processes food more efficiently in the first half of the day. This is when insulin sensitivity—the body’s ability to use glucose—is at its highest.

Benefits of a Heavier Breakfast and Lighter Dinner:

- Improved blood sugar control

- Better weight management

- Increased satiety throughout the day

Example:

- Breakfast: 40% of daily calories

- Lunch: 35%

- Dinner: 25%

4. Limit Nighttime Eating

Eating late at night—especially close to bedtime—can interfere with your sleep and metabolism. Your digestive system slows down at night, making late meals harder to process.

Why Avoid Late Meals?

- Increases fat storage

- Worsens sleep quality

- Disrupts melatonin production

Ideal Cutoff: Try to finish your last meal at least 2–3 hours before bed.

5. Monitor Caffeine and Alcohol Intake

Caffeine can linger in your system for up to 6–8 hours and disrupt your circadian rhythm. Alcohol may initially sedate you but leads to poor sleep quality and disrupts REM cycles.

Timing Tips:

- Avoid caffeine after 2 p.m.

- Limit alcohol to early evening and in moderation

- Opt for herbal teas (like chamomile) to support wind-down routines

6. Plan around Life Demands

Life isn’t always predictable, and rigid eating schedules can be difficult to maintain. However, even small adjustments can help you stay in sync.

Strategies:

- Batch-cook balanced meals for busy days

- Time-restricted eating (e.g., eating within a 10–12 hour window) helps preserve rhythm flexibility

- Adjust gradually to changing work or school schedules—shifting meal times by 15–30 minutes a day can ease transitions

Real-Life Applications

Case 1: Sarah, a Nurse Working Night Shifts

Sarah eats her biggest meal during her shift at 2 a.m., struggles with energy dips, and gains weight. After adjusting her schedule to have a hearty pre-shift meal (6 p.m.), a light snack mid-shift (1 a.m.), and a small breakfast before bed (8 a.m.), she reports better digestion, sustained energy, and improved sleep.

Case 2: James, a Frequent Business Traveler

James used to eat according to his home time zone even after landing. Now, he starts adjusting meal and sleep times two days before his flight, aligning with the destination’s local schedule. He avoids heavy meals on the plane and uses sunlight exposure to reset his body clock faster.

Eat with the Clock, Not Against It

Meal timing is a powerful yet often overlooked tool for health. Aligning you’re eating habits with your body’s circadian rhythms supports optimal digestion, better sleep, stable energy, and a healthier metabolism. Whether you’re dealing with a packed social calendar, irregular shifts, or international travel, the key is to create a rhythm that respects your body’s natural timing.

Start with small, sustainable changes—front-load your calories, eat consistently, and listen to your internal cues. Over time, you’ll find that not only does your body feel better, but your relationship with food becomes more intuitive and aligned.

Conclusion

Synchronizing your meal timing with your biological clock is a powerful yet underutilized health strategy. In a world increasingly dominated by artificial lighting, erratic schedules, and on-demand food delivery, our natural rhythms are often overlooked. However, decades of research on chronobiology underscore the importance of aligning our daily behaviors—including eating patterns—with our internal clocks. Each person has a phonotype that governs their ideal times for sleeping, waking, and performing various activities, including eating. Respecting this biological schedule can lead to profound improvements in metabolic health, energy levels, and overall well-being.

By understanding and respecting your phonotype, you can begin to make meal timing decisions that complement your body’s innate rhythm. Morning phonotypes, for example, may benefit from eating earlier in the day when insulin sensitivity is higher, thereby reducing the risk of weight gain and blood sugar fluctuations. Evening phonotypes, on the other hand, can optimize their meals by shifting caloric intake to match their delayed peak energy hours—though they should still avoid eating late at night to minimize metabolic disruption. Intermediate types, who fall somewhere in between, are encouraged to maintain consistency in their meal schedules and avoid erratic eating habits.

Scientific advancements in the field of chrononutrition continue to reveal how crucial timing is when it comes to health outcomes. It’s not just what we eat, but also when we eat that determines how our bodies process nutrients, regulates hormones, and manages energy. Eating at irregular times, particularly late at night or during the biological night, has been associated with increased risks of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Tailoring your diet to your body’s natural rhythm represents a major step toward personalized wellness. Rather than following one-size-fits-all diet plans, individuals can work with their phonotype to build sustainable eating habits that promote vitality and long-term health. This approach encourages a deeper awareness of the body’s needs and fosters a more intuitive relationship with food.

As our understanding of circadian biology expands, integrating chrononutrition into everyday life will become increasingly feasible—and perhaps essential. Healthcare providers, nutritionists, and wellness coaches are beginning to take notice, suggesting that in the near future, meal timing recommendations based on phonotype could become a staple of preventive healthcare. Embracing this science not only empowers individuals to take charge of their health, but also paves the way for a future in which personalized nutrition plays a central role in medical and lifestyle guidance.

Future research is expected to provide more precise guidelines, helping individuals implement chrononutritional strategies that go beyond generic diet plans. Healthcare professionals, dietitians, and fitness experts may also begin adopting these models into mainstream care.

SOURCES

Rosenberg et al., 2003 – The human circadian clock and its influence on phonotype.

Duffy et al., 1999 – Age-related changes in phonotype.

Garrulity & Gómez-Avella, 2014 – Timing of food intake and obesity.

Poggiogalle et al., 2018 – Circadian rhythms and metabolic health.

Schemer et al., 2009 – Adverse metabolic effects of circadian misalignment.

Green et al., 2008 – Peripheral clocks and feeding schedules.

Wright et al., 2012 – Effects of circadian misalignment on sleep and metabolism.

Morris et al., 2015 – Circadian regulation of metabolism.

Qi an & Schemer, 2016 – Circadian system and glucose regulation.

Sutton et al., 2018 – Early time-restricted feeding and metabolic health.

Wilkinson et al., 2020 – Intermittent fasting and cardiovascular health.

Whitman et al., 2006 – Social jetlag and obesity.

Knutson, 2003 – Health disorders in shift workers.

Waterhouse et al., 2007 – Effects of time zone transitions.

Schemer et al., 2009 – Adverse metabolic effects of circadian misalignment.

Johnston, 2014 – Chrononutrition and metabolic health.

Rosenberg et al., 2012 – Social jet lag and obesity.

Wang et al., 2014 – Shift work and metabolic disorders.

Waterhouse et al., 2007 – Jet lag and gastrointestinal disruption.

Adam et al., 2012 – Phonotype, health, and performance.

Garrulity & Gómez-Avella, 2014 – Timing of food intake and weight loss.

Jakubowicz et al., 2013 – Breakfast size and weight loss.

Kinsey & Ormsbee, 2015 – Nighttime eating and health risks.

Drake et al., 2013 – Caffeine and sleep disruption.

Rohr’s & Roth, 2001 – Alcohol and sleep quality.

Gill & Panda, 2015 – Time-restricted eating and circadian rhythms.

Morris et al., 2016 – Meal timing and glucose control in shift workers.

Arendt, 2009 – Travel, jet lag, and circadian resynchronization.

Leung et al., 2020 – Circadian control of metabolism

HISTORY

Current Version

June 12, 2025

Written By

ASIFA