The Blood Type Diet posits that an individual’s ABO blood type determines their ideal dietary and lifestyle choices. Popularized in the late 1990s by Dr. Peter D’Amato in his book Eat Right 4 Your Type, the diet suggests that aligning your meals with your blood type can improve digestion, increase energy, aid in weight loss, and reduce the risk of chronic diseases.

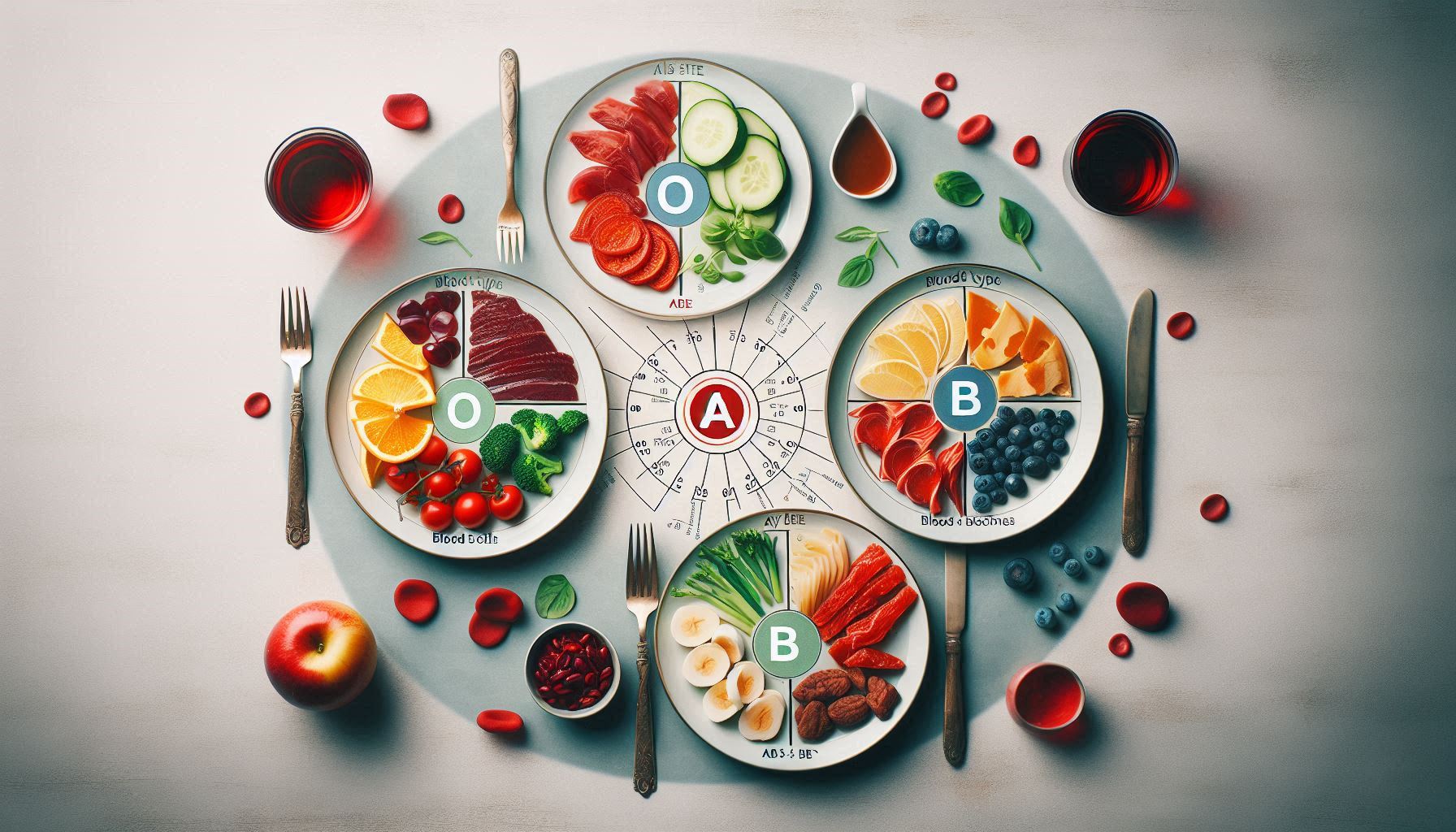

According to the theory, each blood type corresponds to a distinct evolutionary lineage with specific dietary needs:

- Type O is considered the “hunter” and thrives on a high-protein, meat-heavy diet similar to Pale.

- Type A, the “agrarian,” supposedly benefits from a plant-based, vegetarian approach.

- Type B, the “nomad,” can handle a mixed diet including dairy and grains.

- Type AB, a fusion of A and B traits, is advised to eat a flexible combination of both plans.

The core premise involves lections—proteins found in many plant foods—that allegedly interact negatively with certain blood types, causing digestive issues and inflammation. Proponents claim that avoiding incompatible lections leads to improved health outcomes.

However, scientific scrutiny tells a different story. Multiple systematic reviews and clinical trials have found no credible evidence linking blood type to diet-based health benefits. A 2013 review in Plops One concluded that no studies supported the diet’s claims. Similarly, a 2014 study involving over 1,400 participants showed health improvements from various diets, but these were unrelated to blood type.

Additionally, modern genetic research contradicts the diet’s evolutionary narrative. Contrary to D’Amato’s claims, blood type a likely predates type O, and blood types evolved in response to pathogens—not diet.

While some may feel better following the Blood Type Diet, benefits are likely due to eating more whole foods and avoiding processed ones—not because of blood type compatibility. Ultimately, the diet’s appeal lies more in its simplicity and personalization than in scientific accuracy.

In short, while the Blood Type Diet may not be harmful, it remains more nutritional folklore than fact-based practice.

Origins of the Blood Type Diet

The Blood Type Diet was introduced to the public by Dr. Peter J. D’Amato, a naturopathic physician, in his 1996 bestseller Eat Right 4 Your Type. The book proposed that ABO blood groups—a classification of red blood cell antigens—play a vital role in determining how individuals respond to specific foods. According to D’Amato, our blood types mirror the genetic heritage of early human populations, and each type evolved alongside particular dietary environments.

The Four Blood Types and Their Prescribed Diets

D’Amato associates each blood type with an anthropological archetype, prescribing dietary practices based on supposed ancestral eating habits:

- Type O (“The Hunter”)

- Ancestral Claim: The earliest blood type, originating with Paleolithic hunter-gatherers.

- Dietary Prescription: High-protein, low-carb, grain-free diet similar to modern Pale. Emphasizes red meat, fish, and vegetables.

- Restricted Foods: Wheat, legumes, and dairy.

- Type A (“The Agrarian”)

- Ancestral Claim: Emerged with the advent of agriculture.

- Dietary Prescription: Primarily plant-based; akin to vegetarian or Mediterranean diets.

- Restricted Foods: Red meat and dairy.

- Type B (“The Nomad”)

- Ancestral Claim: Linked to nomadic tribes of Central Asia.

- Dietary Prescription: Balanced inclusion of meat, dairy, grains, and vegetables.

- Restricted Foods: Corn, wheat, lentils, and chicken.

- Type AB (“The Enigma”)

- Ancestral Claim: The most recent and rarest blood type, resulting from a mix of A and B.

- Dietary Prescription: A flexible approach combining the recommendations for types A and B.

- Restricted Foods: Red meats and some beans.

This approach suggests that mismatched foods trigger physiological stress, while compatible foods support digestion, immune function, and energy metabolism.

The Scientific Claims behind the Diet

D’Amato’s primary scientific hypothesis rests on the interaction between lections—plant-derived proteins found in foods—and blood type antigens, which are glycoproteins present on the surface of red blood cells and many other cells.

What Are Lections?

Lections are carbohydrate-binding proteins found in a wide variety of foods, especially legumes, grains, and nightshade vegetables. They can bind to cell membranes and, in high amounts, may disrupt digestive function or contribute to inflammation. However, this potential is largely neutralized by cooking and proper food preparation.

The Core Hypothesis

According to D’Amato, different blood types react differently to lections. For example:

- A person with type a blood eating foods high in certain lections (e.g., red meat or dairy) might experience blood cell agglutination (clumping), inflammation, or digestive upset.

- Conversely, consuming “compatible” foods would avoid these reactions, promoting well-being.

Scientific Counterarguments

- Lack of Mechanistic Proof: While lections can cause agglutination in in vitro experiments, there’s no evidence that dietary lections selectively bind to blood type antigens in vivo in a way that causes systemic harm.

- Denaturation of Lections: Most lections are destroyed or rendered harmless by soaking, cooking, or fermenting. Therefore, their potential to harm the digestive tract is minimal for properly prepared foods.

- Generalization across Populations: The assumption that every individual with a specific blood type has uniform reactions to foods oversimplifies the complexity of digestion, immunity, and metabolism.

In essence, the diet’s theoretical framework, while intriguing, lacks empirical grounding in human physiology and immunology.

The Research Landscape

Despite its popularity, the Blood Type Diet has been widely criticized by the scientific and medical communities for lacking rigorous, peer-reviewed support.

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

The most comprehensive analysis comes from a 2013 systematic review published in Plops One by Cusack et al. It concluded:

“No evidence currently exists to validate the purported health benefits of the Blood Type Diet.”

The review examined hundreds of publications and failed to find even a single well-controlled study demonstrating that blood-type-specific diets produce superior health outcomes. This finding is critical, as systematic reviews represent the highest level of scientific evidence.

Clinical Trials

A handful of experimental studies have attempted to test the diet’s validity in a clinical setting.

- 2014 (American Journal of Clinical Nutrition):

A team led by Ahmed El-Seamy at the University of Toronto analyzed health data from 1,455 participants. They found:

Individuals following vegetarian or high-protein diets improved their metabolic markers, regardless of their blood type.

The study concluded that the observed benefits were due to the diet itself—not its alignment with blood type.

- 2021 (Journal of Nutrition & Metabolism):

A plant-based intervention trial showed cardiovascular and digestive improvements across all participants. However, these benefits were not correlated with blood type. The authors emphasized that dietary quality—not blood type—was the likely cause of improved outcomes.

These findings challenge the diet’s core premise: that matching diet to blood type provides unique health benefits.

Epidemiological and Population-Based Studies

Large-scale demographic research also undermines the diet’s assumptions:

- A 2020 study in Lancet Regional Health reviewed global epidemiological data and found:

No statistically significant correlation between ABO blood types and the prevalence of metabolic conditions such as diabetes, obesity, or digestive disorders.

- Additional research into blood type distributions across regions with varying dietary habits (e.g., rice-based diets in East Asia vs. dairy-heavy diets in Northern Europe) shows no consistent pattern of disease risk or health outcomes linked to blood type.

The epidemiological record does not support the idea that individuals with certain blood types are better suited to specific macronutrient profiles or food categories.

Debunking the Evolutionary Premise

A major appeal of the Blood Type Diet is its ancestral narrative—that blood types reflect evolutionary adaptations to specific diets. However, this theory is biologically flawed.

D’Amato’s Evolutionary Model:

- Type O as the “original” blood type, tied to Paleolithic hunter-gatherers.

- Type A emerged during the rise of agriculture.

- Type B developed with nomadic dairy-consuming peoples.

- Type AB appeared from the mingling of A and B groups.

What Genetic Research Actually Shows:

- Genomic studies published in Nature Genetics (2009) demonstrate that type a likely predates type O, reversing the timeline presented in D’Amato’s hypothesis.

- The ABO gene exists in primates and early hominids, suggesting that blood types evolved long before modern dietary practices emerged.

- Human blood types are maintained through a complex balance of selective pressures, including pathogen resistance—not dietary compatibility.

Moreover, the concept that blood type evolution aligns neatly with dietary shifts lacks support in archaeological and anthropological records. Populations across all blood types have thrived on a wide array of diets throughout history.

Expert Opinions

- Harvard Health Publishing (2019): Finds no evidence linking blood type with dietary needs.

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (2021): Considers the diet restrictive and unsupported by science.

- Cleveland Clinic (2020): Labels the diet a myth with misleading claims.

- Mayo Clinic (2022): States there is no scientific backing for blood type diet theories.

- British Dietetic Association (BDA, 2022): Declares the blood type diet a nutrition myth.

Real-World Observations

The Blood Type Diet, despite being widely criticized and lacking robust scientific validation, remains popular. Many adherents claim noticeable improvements in their health—better digestion, more energy, weight loss, and fewer digestive complaints. These testimonials, though anecdotal, can be persuasive.

So, why do people feel better on a diet that scientists have largely debunked?

The answer lies not in the specificity of blood type matching, but in a combination of healthier food choices, greater dietary awareness, and psychological effects. Below, we unpack the real reasons why the Blood Type Diet might lead to perceived or real health improvements—and why these benefits aren’t exclusive to the ABO classification system.

Reduction in Processed Foods

One of the most powerful mechanisms behind feeling better on the Blood Type Diet is that it naturally eliminates or reduces ultra-processed foods.

Each of the Blood Type recommendations—regardless of blood group—discourages:

- Refined sugar

- Artificial additives and preservatives

- Highly processed meats

- Hydrogenated oils

- White flour products

These are the very foods implicated in promoting obesity, inflammation, insulin resistance, and gut symbiosis. Even without personalized tailoring, simply reducing or eliminating these foods can produce:

- Improved blood sugar stability

- Reduced bloating and GI discomfort

- Fewer energy crashes

- Better weight control

For example, a Type Of person eliminating bread and processed grains might experience less bloating—not because of blood type incompatibility, but because of reduced gluten or FODMAP intake. Similarly, a Type an individual shifting to more plant-based foods might consume more fiber and antioxidants, improving digestion and systemic inflammation.

In this way, the health benefits arise from a universally better diet, not from unique lection-blood type interactions.

Increased Intake of Whole Foods

The Blood Type Diet encourages people to eat more:

- Fresh vegetables

- Lean proteins (fish, poultry, legumes)

- Fruits and whole grains (depending on type)

- Nuts, seeds, and healthy fats

This shift from processed to whole foods brings a nutrient-dense eating pattern that supports nearly every physiological system. Common results include:

- Better micronutrient intake (e.g., magnesium, potassium, vitamin C)

- Increased fiber for gut health and regularity

- Lower intake of pro-inflammatory omega-6 fats

- A healthier omega-3/omega-6 ratio

For instance, an individual following the Type B or AB diet is often consuming a balanced meal plan that naturally supports metabolic health, whether or not their blood type is biologically connected to that pattern.

In effect, the Blood Type Diet mimics aspects of other proven healthy diets (such as Mediterranean, DASH, or Whole30), without scientific justification for blood group differentiation.

Greater Dietary Awareness and Mindful Eating

Following the Blood Type Diet requires people to pay closer attention to:

- What they eat

- How often they eat

- How food makes them feel

This type of mindfulness can lead to significant improvements in overall well-being. Research shows that mindful eating is associated with:

- Lower calorie consumption

- Fewer episodes of emotional eating

- Improved relationship with food

- Better digestion and satiety recognition

By making followers more intentional and deliberate about food choices, the Blood Type Diet introduces a kind of self-regulation mechanism. People slow down, read labels, plan meals, and track food quality—all habits that support health.

Importantly, this happens regardless of blood type; the effect stems from behavioral changes, not biological compatibility.

The Power of the Placebo Effect

The placebo effect is a well-documented psychological phenomenon in which belief in a treatment’s effectiveness can lead to real or perceived improvement, even when the treatment has no therapeutic value.

The Blood Type Diet comes wrapped in a compelling narrative:

- It claims to personalize nutrition

- It invokes genetics and evolution

- It offers certainty in a confusing dietary landscape

This narrative gives people a sense of control and clarity, which is emotionally satisfying. As a result, adherents may:

- Expect to feel better

- Notice positive changes more readily

- Ignore symptoms or fluctuations

- Attribute improvements to the diet rather than other factors

Belief, expectation, and the ritual of following a “scientific-sounding” system create a fertile ground for the placebo effect to flourish. While these improvements are not based on the diet’s scientific validity, they are still psychologically meaningful.

Improved Gut Health (by Chance)

Some blood type prescriptions inadvertently align with evidence-based approaches for gut health. For example:

- Type A’s vegetarian emphasis increases prebiotic fiber

- Type O’s avoidance of wheat may help those with non-celiac gluten sensitivity

- Type B’s inclusion of fermented dairy could support gut micro biota

- Type AB’s moderation may reduce digestive irritants

These benefits aren’t due to blood type compatibility, but to accidental alignment with known digestive strategies.

Also, any diet that reduces sugar and processed food will starve pro-inflammatory gut bacteria and support a healthier micro biome, improving:

- Regularity

- Nutrient absorption

- Immune modulation

Hence, improvements in gut function often attributed to the Blood Type Diet are likely due to better overall food quality and reduced gut irritants, not blood type per se.

Weight Loss through Caloric Control

Many people report weight loss after starting the Blood Type Diet. This effect is not surprising when you consider:

- Elimination of high-calorie, low-nutrient foods

- Reduction in liquid calories (sodas, sweetened drinks)

- Less snacking due to structured meal patterns

- Increased consumption of satiating proteins and fibers

These dietary changes naturally lead to lower total caloric intake, even if individuals aren’t counting calories explicitly. Sustained caloric deficits—combined with better food quality—is the true engine behind most weight loss results seen in Blood Type Diet followers.

Behavior Change and Identity

Engaging with the Blood Type Diet provides something many other diets do not: a personalized identity. Being “a Type An eater” or “a Type Of person” gives people:

- A sense of belonging

- A clear set of rules

- A structured lifestyle framework

Psychologically, this can be empowering. People often stick to diets longer when they feel they are part of a system that’s uniquely tailored to them—even if that tailoring is fictional.

This identity-based behavior change reinforces discipline, enhances motivation, and creates a feedback loop of perceived success.

Confirmation Bias and Selective Memory

Human beings are prone to confirmation bias—we remember information that supports our beliefs and forget data that contradicts them. In the context of the Blood Type Diet:

- People notice when they feel good and attribute it to dietary compliance.

- They overlook symptoms that persist, or blame “cheating” for setbacks.

- They often fail to objectively assess their health markers (e.g., blood pressure, labs).

This mental filtering creates a perception of success, especially when health improvements (even minor or coincidental) occur around the time of starting the diet.

The Benefits Are Real—but Not Because of Blood Type

It’s clear that people may genuinely feel better on the Blood Type Diet—but the reasons have little to do with matching foods to blood types. Instead, these benefits stem from:

- Eating fewer processed foods

- Choosing more vegetables and lean proteins

- Becoming more mindful about eating habits

- Experiencing psychological empowerment and expectation-based improvement

- Making behavioral changes tied to identity and structure

Risks and Downsides

| Issue | Explanation |

| Nutritional Deficiency | Some blood types are advised to avoid entire food groups. |

| Restriction | Limits flexibility, especially in social and cultural contexts. |

| Cost | Specialized foods and supplements can be expensive. |

| Pseudoscience | May distract from evidence-based dietary guidance. |

Popularity in Media and Culture

The Blood Type Diet is an enduring example of a nutrition theory with mass appeal but limited scientific credibility. While its storytelling is compelling—blending evolutionary biology, immunology, and personalized health—its claims are not supported by clinical, epidemiological, or genetic evidence.

Modern nutritional science increasingly emphasizes personalized nutrition, but this personalization must be rooted in evidence-based metrics like metabolic biomarkers, gut micro biome profiles, and genetic predispositions—not blood type alone.

Until more rigorous research supports the diet’s core principles, it should be approached with skepticism. Individuals seeking dietary guidance are better served by consulting registered dietitians and using validated tools rather than relying on unsupported theories.

Better Alternatives

- Mediterranean Diet: Rich in vegetables, whole grains, and healthy fats.

- DASH Diet: Effective for hypertension, promotes balanced nutrients.

- Plant-Based Diets: Support heart and metabolic health regardless of blood type.

- Nutrigenomic Diets: Based on gene expression rather than blood type.

Personalized Nutrition: A Better Paradigm

Rather than blood type, nutrition should be based on:

- Genetic testing (nutrigenomics)

- Micro biome composition

- Personal health history

- Lifestyle and culture

This approach is backed by emerging nutritional science and allows more precise dietary strategies.

Conclusion

The concept of the blood type diet has captivated public imagination for decades, blending pseudo-historical narratives, anecdotal endorsements, and dietary restrictions into a framework that promises personalized health. However, a careful review of the scientific literature reveals that while the diet may result in short-term improvements in health behaviors; these outcomes are largely independent of blood type. Instead, they stem from general principles of clean eating—minimizing processed foods, emphasizing whole ingredients, and increasing nutrient-dense meals.

Multiple peer-reviewed studies, including work published in Plops One (2013) and the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2014), show no evidence that tailoring diet based on ABO blood type offers any metabolic, cardiovascular, or digestive advantage. Leading institutions such as Harvard Health Publishing, the Cleveland Clinic, and the British Dietetic Association have dismissed the theory due to the lack of empirical support and its potential to mislead the public.

Furthermore, evolutionary and genetic arguments used to rationalize the diet—such as the idea that blood types evolved in tandem with historical dietary shifts—have been debunked. Genomic analyses demonstrate that blood types do not align with the hunter-versus-farmer dichotomy promoted by D’Amato. In fact, Type A predates Type O, contradicting the central premise of the diet’s lineage-based classification.

Despite these findings, many people remain attracted to the blood type diet because it appears structured, personalized, and backed by selective biological reasoning. It also benefits from celebrity endorsements and the public’s growing appetite for personalized nutrition. However, personalization in modern nutrition is better achieved through evidence-based approaches such as nutrigenomics, micro biome analysis, and metabolic profiling, rather than ABO blood group assignment.

The diet’s restrictive nature may lead to nutritional deficiencies, unnecessary elimination of beneficial foods, and psychological stress due to rigid adherence. Worse, it may divert attention away from truly effective dietary patterns like the Mediterranean or DASH diets, which are supported by decades of robust clinical research and epidemiological data.

In summary, the blood type diet is best viewed not as a scientifically valid method of improving health, but as a fad diet that capitalizes on the illusion of personalization. The path forward lies in advancing personalized nutrition through validated science, ensuring individuals receive dietary recommendations that reflect their unique biological and lifestyle factors—not their blood type.

SOURCES

Harvard Health Publishing (2019): “Do Blood Type Diets Really Work?”

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2014): “Blood Type Diet Study in Young Adults”

Plops One (2013): “Lack of Empirical Support for Blood Type Diet Hypothesis”

Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (2021): Position Papers on Diet and Health

Cleveland Clinic (2020): “Myth-Busting the Blood Type Diet”

Journal of Nutrition & Metabolism (2021): “Effects of Plant-Based Diet Independent of Blood Type”

Lancet Regional Health (2020): “Global Epidemiological Study on Blood Types and Disease Risk”

Nature Genetics (2009): “The Evolution of ABO Blood Types”

British Dietetic Association (2022): “Top 5 Nutrition Myths”

Mayo Clinic (2022): “Blood Type Diet Overview”

Nutrition Reviews (2021): “Evaluating Popular Diet Claims”

BMJ Nutrition, Prevention & Health (2020): “Critical Review of Dietary Fads”

Johns Hopkins Medicine (2020): “What to Know About Diet Trends”

Tufts University Health & Nutrition Letter (2019): “Blood Type Diet: Myth or Fact?”

Stanford Medicine (2021): “Precision Health in Nutrition”

NIH Medline Plus (2020): “Truth About Diets”

World Health Organization (2021): “Dietary Guidelines and Global Health”

University of Sydney Nutrition Studies (2018): “Debunking the Blood Type Diet”

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2022): “Does Blood Type Influence Dietary Response?”

HISTORY

Current Version

June 13, 2025

Written By

ASIFA