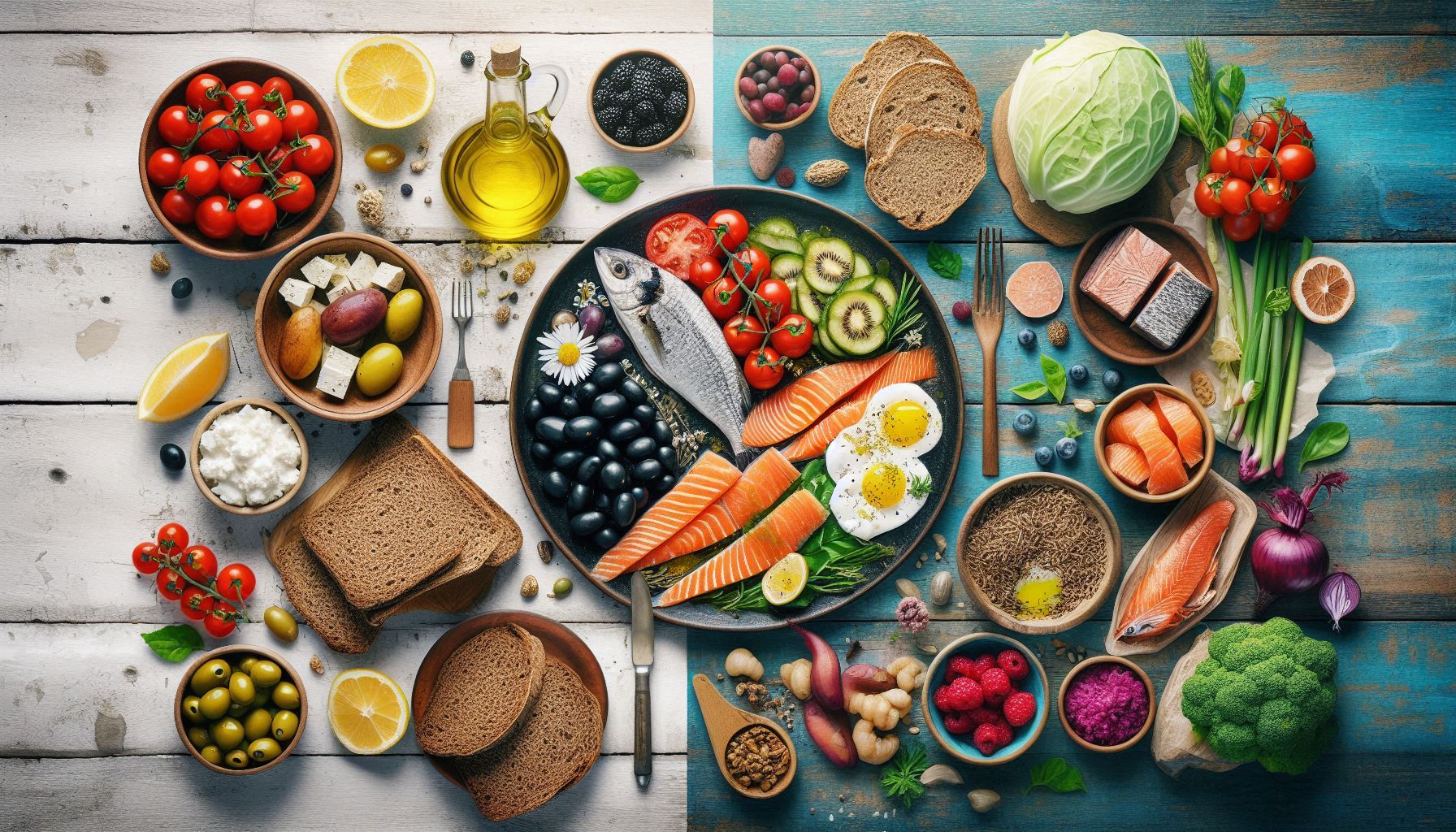

In a world increasingly focused on health, longevity, and environmental sustainability, two regional diets have gained prominence for their impressive blend of nutritional value and culinary richness: the Mediterranean and Nordic diets. Both dietary patterns emphasize whole foods, plant-based ingredients, and healthy fats, aligning well with modern concerns about chronic disease prevention and ecological impact. Though similar in many ways, these diets originate from distinct geographical, cultural, and environmental backgrounds, shaping their unique food traditions and health philosophies.

The Mediterranean diet, rooted in the coastal cuisines of Southern Europe—particularly Greece, Italy, and Spain—has been extensively studied for decades. It champions a balanced, varied intake of fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains, nuts, and seeds, complemented by olive oil as the primary fat source. Moderate consumption of fish, poultry, dairy, and red wine is also characteristic. Its appeal lies not only in its heart-healthy reputation but also in its social and lifestyle context, which includes shared meals and physical activity. Scientific research has consistently linked the Mediterranean diet with lower risks of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, certain cancers, and cognitive decline.

The Nordic diet, while newer to the global conversation, is no less compelling. Originating from Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden, it reflects the natural abundance and culinary traditions of Northern Europe. Like the Mediterranean model, the Nordic diet emphasizes plant-based eating, but it focuses on locally available foods such as root vegetables, whole grains like rye and barley, berries, cabbage, and fatty fish including herring and salmon. It uses canola oil (rapeseed oil) instead of olive oil and encourages minimal consumption of red meat and processed foods. Early studies suggest it may offer comparable benefits to the Mediterranean diet, particularly in improving blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and weight management.

The health effects of both diets stem from their anti-inflammatory properties, high fiber content, low glycemic load, and rich supply of antioxidants and omega-3 fatty acids. These mechanisms help regulate blood sugar, reduce harmful cholesterol, support gut health, and protect against oxidative stress. Both diets encourage sustainable eating patterns by emphasizing seasonal, locally grown foods and limiting highly processed items and animal products—factors critical in reducing the environmental footprint of modern diets.

Sustainability is a growing concern, and this is where the Nordic diet offers a unique advantage for populations in colder, temperate climates. Its emphasis on regional and seasonal produce makes it more environmentally aligned in such contexts, reducing reliance on imported foods. The Mediterranean diet, though also sustainable, may be less practical in areas where Mediterranean crops like olives and citrus are not locally available.

When it comes to practical application, both diets are flexible, accessible, and culturally rich, offering flavorful meals without rigid restrictions. Ultimately, choosing between the Mediterranean and Nordic diets may come down to individual preference, cultural background, and local food availability.

Rather than competing, these two diets represent adaptable models of healthy, sustainable eating. Each offers a blueprint for long-term wellness, making them equally valuable depending on context. Whether by the sun-drenched shores of the Mediterranean or the cool forests of Scandinavia, both diets illuminate a path toward better health and a more sustainable future.

Origins and Cultural Context

In an age where chronic diseases and climate concerns dominate global health conversations, dietary habits are receiving unprecedented attention. Among the many eating patterns promoted for health and sustainability, the Mediterranean and Nordic diets have emerged as two of the most respected. Each rooted in its own geography and cultural heritage, these diets share a commitment to whole, plant-forward eating and minimal processing. But while they overlap in many principles, their differences—shaped by history, agriculture, and climate—offer unique insights into how regional food systems can support both human and planetary health.

Origins and Evolution

Mediterranean Diet

The Mediterranean diet originated in countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea, notably Greece, Italy, and Spain. It reflects a centuries-old tradition of consuming foods that are fresh, minimally processed, and abundant in nutrients. Though this way of eating had been practiced for generations, it gained international recognition in the 1950s, thanks to the work of Ankle Keys and other researchers. They observed that Mediterranean populations, especially in southern Italy and Crete, had significantly lower rates of coronary heart disease compared to populations in Northern Europe and the United States.

Keys’ findings led to decades of nutritional and epidemiological research, eventually cementing the Mediterranean diet as a model for heart-healthy living. Its emphasis on olive oil, fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and fish, alongside moderate wine intake and limited red meat, formed the basis for numerous public health recommendations globally.

Nordic Diet

In contrast, the Nordic diet is a more recent development, formally introduced in the early 2000s through a collaborative effort involving nutritionists, chefs, and environmental researchers in Scandinavia. Countries such as Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Iceland sought to revive their traditional culinary practices while aligning them with modern nutrition science and sustainability goals. The result was the New Nordic Diet, a modern adaptation that values local, seasonal, and sustainable foods.

Drawing on the region’s native agriculture and ecosystems, the Nordic diet emphasizes root vegetables, cabbage, berries, whole grains like rye, oats, and barley, legumes, rapeseed (canola) oil, and fatty fish such as herring and salmon. Unlike the Mediterranean model, which emerged organically, the Nordic diet was intentionally crafted to address both health outcomes and environmental stewardship.

Core Principles and Components

Though the Mediterranean and Nordic diets share foundational elements—such as plant-based focus, healthy fats, and minimally processed ingredients—their specific components reflect their regional biodiversity and food cultures.

| Aspect | Mediterranean Diet | Nordic Diet |

| Primary fat source | Olive oil | Rapeseed (canola) oil |

| Main grains | Wheat, faro, bulgur | Rye, barley, oats |

| Vegetables | Tomatoes, leafy greens, eggplant, zucchini | Root vegetables (carrots, beets), cabbage, potatoes |

| Fruits | Citrus, grapes, figs | Berries (lingo berries, blueberries) |

| Protein sources | Fish, legumes, limited poultry, occasional red meat | Fatty fish (salmon, herring), legumes, low-fat dairy, lean meats |

| Dairy | Moderate cheese and yogurt | Low-fat dairy, skier |

| Alcohol | Moderate wine consumption | Minimal alcohol emphasis |

| Herbs & spices | Basil, oregano, garlic, rosemary | Dill, juniper, mustard seeds |

Both diets avoid processed foods, sugar-sweetened beverages, and excessive red meat, supporting not only human health but also reduced environmental impact.

Health Benefits and Scientific Backing

Mediterranean Diet

The Mediterranean diet has been extensively studied for over six decades. Landmark studies such as the Seven Countries Study, PREDIMED trial (Spain), and numerous meta-analyses have shown consistent health benefits. These include:

- Cardiovascular Health: Lower incidence of heart disease and stroke.

- Metabolic Benefits: Improved insulin sensitivity and reduced risk of type 2 diabetes.

- Weight Management: Helps prevent obesity and promotes a healthy BMI.

- Brain Health: Reduced risk of cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease.

- Cancer Prevention: Inverse associations with certain cancers (e.g., colorectal, breast).

Nordic Diet

Though newer, the Nordic diet is quickly gaining scientific credibility. Studies like OPUS (Denmark) and SYSDIET (Finland) have investigated its effects. Emerging evidence supports benefits such as:

- Improved lipid profiles: Reduction in LDL cholesterol and triglycerides.

- Blood Pressure Control: Linked to lower systolic and diastolic blood pressure.

- Weight Regulation: May support satiety and healthy weight loss.

- Glycemic Control: Helps regulate blood sugar levels, reducing diabetes risk.

- Anti-inflammatory Effects: Similar to the Mediterranean diet, rich in antioxidants and omega-3s.

While the Mediterranean diet currently has more robust long-term data, the Nordic diet is showing promising, comparable results in Northern European populations.

Mechanisms of Action

Both diets work through several shared and distinct physiological mechanisms:

- High in Fiber: Promotes gut health, lowers cholesterol, and stabilizes blood glucose.

- Rich in Antioxidants: Protects against oxidative stress, a driver of aging and chronic disease.

- Healthy Fats: Olive oil and rapeseed oil are rich in monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats, supporting heart health.

- Anti-inflammatory: Both diets are naturally anti-inflammatory due to their focus on plant-based foods and fatty fish.

- Low in Processed Foods: Reduces intake of added sugars, refined grains, and Trans fats—all major contributors to chronic illness.

Sustainability and Environmental Impact

One of the most forward-thinking aspects of the Nordic diet is its deliberate focus on sustainability. Developed with environmental concerns in mind, it prioritizes:

- Local food sourcing

- Reduced meat consumption

- Lower carbon footprint crops

- Seasonal eating

- Minimal food waste

Because it’s adapted to northern climates, the Nordic diet can be more sustainable in these regions compared to importing Mediterranean staples like olives, avocados, or citrus fruits.

The Mediterranean diet, while less explicitly eco-focused in its origins, also aligns with sustainable eating principles due to its plant-based emphasis and lower reliance on industrially processed foods or red meat. However, its full environmental benefit may depend on regional adaptation—for example, sourcing local olive oil alternatives where olives don’t grow naturally.

Cultural Integration and Practicalities

Mediterranean Diet in Daily Life

With its warm, communal eating style, the Mediterranean diet often includes:

- Family meals

- Home-cooked dishes

- Leisurely eating pace

- Simple, rustic preparations

Foods like pasta with tomato sauce, lentil soup, grilled fish, and Greek salad are easy to prepare and widely enjoyed, even beyond Mediterranean borders.

Nordic Diet in Practice

The Nordic diet is practical, particularly in colder regions. Its foods—like hearty vegetable stews, rye bread, pickled fish, and root vegetable dishes—are naturally suited for preservation and seasonal cooking. It’s increasingly being integrated into public health initiatives and school meal programs in Scandinavian countries.

Both diets are adaptable to vegetarian, piscatorial, and flexitarian lifestyles. Their accessibility makes them attractive for global adaptation with regional modifications.

Complementary, Not Competing

When comparing the Mediterranean and Nordic diets, it’s not about choosing one over the other. Rather, both represent regionally rooted, scientifically validated, and nutritionally sound frameworks for eating. The Mediterranean diet stands on decades of research and global appeal, while the Nordic diet brings a modern, environmentally aligned approach suitable for northern climates and contemporary challenges. The best diet may depend on one’s geography, cultural preferences, and access to ingredients. What unites both is their emphasis on whole foods, plants, healthy fats, and sustainability—a formula for health that transcends borders.

Whether enjoying a sun-ripened tomato salad with olive oil on the coast of Sicily, or a bowl of warm rye porridge with berries in Stockholm, both diets offer a path to holistic well-being that respects both body and planet.

Dietary Composition and Food Groups

Both diets share an emphasis on plant-based foods and fish but differ in key fat sources and staple ingredients.

- Fats:

- Mediterranean: Olive oil (especially extra virgin) is the primary fat source, rich in monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) and polyphenols.

- Nordic: Uses rapeseed (canola) oil, which has a favorable omega-6 to omega-3 ratio and is also rich in MUFA.

- Protein:

- Mediterranean: Lean protein from fish, seafood, legumes, and limited red meat.

- Nordic: Similar protein sources, but includes more game meats and low-fat dairy.

- Carbohydrates and Grains:

- Mediterranean: Emphasizes whole grains like bulgur, faro, and whole wheat bread.

- Nordic: Focuses on high-fiber grains such as rye, barley, and oats.

- Vegetables and Fruits:

- Mediterranean: Tomatoes, leafy greens, citrus fruits, peppers, and onions.

- Nordic: Root vegetables (carrots, beets), cabbages, and berries (lingo berries, bilberries).

- Alcohol and Beverages:

- Mediterranean: Moderate wine, particularly red, often with meals.

- Nordic: Alcohol not emphasized; when consumed, it includes beer or aquavit, but not as a dietary staple.

Health Effects and Clinical Evidence

- Cardiovascular Health

- Mediterranean Diet: Landmark trials like PREDIMED have shown up to a 30% reduction in cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk.

- Nordic Diet: Studies like the NORDIET and SYSDIET trials demonstrate reductions in LDL cholesterol, blood pressure, and inflammation markers, though effects are generally less robust than Mediterranean findings.

- Metabolic Health

- Both diets improve insulin sensitivity and reduce type 2 diabetes risk. The Nordic diet has shown modest weight loss effects, while the Mediterranean is linked to long-term weight maintenance.

- Cognitive Function

- Mediterranean: Strong evidence of protection against cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease, likely due to high polyphenol intake and anti-inflammatory effects.

- Nordic: Emerging evidence suggests similar benefits, particularly from berry polyphenols and omega-3-rich fish.

- Inflammation and Immune Response

- Both diets lower C-reactive protein (CRP) and other inflammation markers. The Mediterranean’s extensive use of olive oil and leafy greens gives it a slight edge.

- Cancer and Longevity

- Mediterranean: Associated with lower rates of breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer, as well as increased lifespan.

- Nordic: Early data show promise in longevity and reduced chronic disease incidence.

Mechanisms of Action

Both diets offer anti-inflammatory, antioxidant-rich eating patterns, but differ slightly in mechanisms:

- Fatty Acids: Mediterranean’s MUFA from olive oil and omega-3 from fish; Nordic’s better omega-3/6 balance from canola oil and fatty fish.

- Polyphenols: Mediterranean sources include wine, olives, vegetables; Nordic focuses on berries, herbs, and root vegetables.

- Fiber: Both diets provide high fiber from grains and vegetables, promoting gut health.

- Micronutrients: High intake of vitamins (A, C, E, K) and minerals (magnesium, selenium, zinc) from plant diversity.

Environmental and Sustainability Aspects

Both diets emphasize sustainability:

- Mediterranean Diet: Seasonal produce, traditional farming methods, less red meat.

- Nordic Diet: Locally sourced, climate-appropriate foods, sustainable seafood, and reduced environmental footprint.

Cultural Feasibility and Adherence

- Mediterranean: Easier to implement in temperate climates, culturally supported in Southern Europe, flexible globally.

- Nordic: Better suited for colder climates; growing popularity due to its alignment with modern nutrition science.

Practical Applications and Menu Ideas

- Mediterranean Sample Day:

- Breakfast: Greek yogurt with honey and walnuts

- Lunch: Chickpea and tomato salad with olive oil

- Dinner: Grilled sardines, faro, sautéed spinach

- Nordic Sample Day:

- Breakfast: Oatmeal with lingo berries and flaxseeds

- Lunch: Rye bread with herring and pickled vegetables

- Dinner: Baked salmon, roasted root vegetables, barley salad

Conclusions

Both the Mediterranean and Nordic diets offer substantial health benefits, particularly due to their emphasis on whole foods, healthy fats, and a predominantly plant-based approach to eating. These dietary patterns encourage the consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds, while minimizing highly processed foods, added sugars, and unhealthy fats. They also promote mindful eating and sustainability, making them not only beneficial for personal health but also for the environment.

The Mediterranean diet has long been the gold standard in nutritional science, backed by decades of robust research. It has consistently been associated with reduced risks of heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and certain types of cancer. This diet includes moderate consumption of fish and poultry, abundant use of olive oil as the primary fat source, and red wine in moderation. The high content of antioxidants, fiber, and omega-3 fatty acids contributes to its protective effects on cardiovascular and cognitive health.

In contrast, the Nordic diet is a more recent but increasingly recognized alternative that reflects the culinary traditions of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. It shares many similarities with the Mediterranean diet but incorporates region-specific ingredients like rye bread, root vegetables, berries, canola oil, and fatty fish such as salmon and herring. What sets the Nordic diet apart is its strong alignment with environmental sustainability and local food systems. It is designed to be both health-promoting and ecologically responsible, making it particularly suitable for individuals living in Northern Europe or areas with similar climates.

While the Mediterranean diet currently enjoys more extensive scientific validation, the Nordic diet presents a compelling, culturally relevant model for healthy living that aligns with both personal wellness and planetary health. Both diets offer practical, long-term strategies for improved nutrition, making them excellent choices depending on individual needs and regional contexts.

SOURCES

Estrus et al., 2013 – PREDIMED Trial

Camera et al., 2014 – SYSDIET Study

Adamson et al., 2011 – Nordic Diet on Weight Loss

Esposito et al., 2009 – Mediterranean Diet for Metabolic Syndrome

Scares et al., 2006 – Mediterranean Diet and Alzheimer’s

Kesse-Guyot et al., 2013 – Dietary Patterns and Cognition

Gross et al., 2014 – Mediterranean Diet and Inflammation

Trichopoulou et al., 2003 – Mediterranean Diet and Mortality

Beer & Burg, 2009 – Nordic Diet and Chronic Disease

Martinez-Gonzalez et al., 2014 – Fiber and Mediterranean Diet

Bach-Fig et al., 2011 – Mediterranean Pyramid Revisions

Bernini et al., 2015 – Mediterranean Diet and Sustainability

Mitral et al., 2012 – New Nordic Diet and Environment

Sofa et al., 2008 – Mediterranean Diet Meta-Analysis

Uusitupa et al., 2013 – Nordic Diet Clinical Trial Review

Tap sell et al., 2010 – Mediterranean Diet and Evidence

Herne et al., 2017 – Mediterranean Diet and HDL Functionality

Roes et al., 2014 – Olive Oil and Cardiovascular Risk

Turner et al., 2017 – Nordic Diet and Obesity Prevention

Pounds et al., 2011 – Adherence to Mediterranean Diet

HISTORY

Current Version

June 14, 2025

Written By

ASIFA